WHEN OPEN AND OBVIOUS ISN'T OPEN AND OBVIOUS

WHAT ARE THE IMPLICATIONS FOR PROVIDING PRODUCT WARNINGS?

It is almost axiomatic in the field of warnings, supported by Federal Codes and Regulations as well as most states’ litigation codes, that product warnings are not required for hazards that are so open and obvious that the typical consumer or employee would recognize the hazard without an oral or written (or both) warning to put the person at risk on notice, so, hopefully, they can make an informed choice, the ultimate goal of most warnings. The classic example taught in most law schools is that we don’t have to warn consumers and product users that knives are sharp because that fact should be readily apparent to the typical knife purchaser and/or user. Most newborn’s parents would support the claim that playing with matches can lead to starting a fire which may have dire consequences for all involved. Although most new parents don’t expect their infants to be aware of this (or any) hazard, my wife, Marylynn and I spent many hours of our two children’s early childhood engaging them in demonstrations and hard lessons of the dangers of fires, a lesson they have carried with them for decades, and, as a result, would be hard pressed to deny the open and obvious nature of a fire hazard and the conditions under which it presents itself.

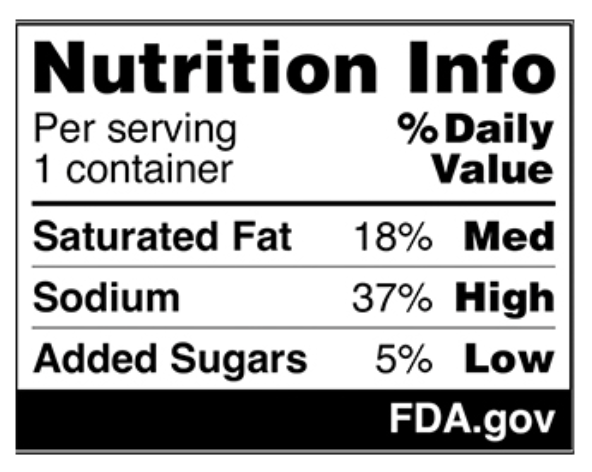

Unlike my children’s learning curve that led, in their case, to a wise conclusion about the hazards of fire, with many products, the hazards, despite claims of defense attorney advocates that the product’s hazard in question (whether it’s a knife, hot coffee, diving into shallow water, misusing a major piece of equipment on a construction site, consuming excessive amounts of added sugar in our diets or, on the lighter side, folding an infant’s carriage without removing the infant (which actually won an award one year for the silliest warning in the U.S.), upon closer inspection and research, may NOT be so open and obvious, and thus may actually need warnings to alert consumers to the real hazard(s). This newsletter will also highlight the balance warnings experts typically seek when trying NOT to dilute the safety landscape with truly open and obvious and, thus, unnecessary warnings, while at the same time, attempting to develop warnings for hazards that, while not deeply hidden from consumers, still haven’t shed enough light on the hazard to provide consumers with the informed choice they should always be entitled to prior to buying and/or using a product. And this challenge is multiplied when the product is used at the workplace where supervisors and/or co-workers, knowledgeable about a product’s hazard (from training, certification, operator manuals, industry codes/standards or government regulations), exercise authority over new or temporary employees (who aren’t typically exposed to the above information) but, nevertheless, are asked or ordered to do work assignments that may place them at risk for injury or death, but haven’t been told anything about the potential hazard(s), and thus are denied the opportunity to make an informed choice. This is particularly harmful, since it would deny this employee the right to refuse to do any job that he or she believes may put them in harm’s way. Let’s use some examples to illustrate my main point that too often the claim of “open and obvious hazard” may be much more nuanced than what might initially have been assumed.

Let’s take the case, taught regularly in many law schools, of the infamous claim in 1992 by McDonald’s that it was open and obvious that their coffee was hot when 79 year old Stella Liebeck, after buying a cup of coffee at a McDonald’s drive-through window in Albuquerque, NM, spilled her coffee on her lap, while stopped in the parking lot to add sugar and cream, and suffered very serious third-degree burns. After several weeks of lambasting poor Stella as the poster child for frivolous lawsuits, including almost nightly taunts from late night comedy hosts, Jay Leno and David Letterman, the truth started to leak out, mostly thanks to trial documents. It turns out that McDonald’s own market research had found that coffee drinkers wanted their coffee just as hot when they got to work as when they picked it up at their local McDonald’s drive-through window. In order to satisfy their consumers, they decided to raise the temperature of their coffee 30-40 degrees higher than their competitors, reaching temperatures as unbelievably high as 190 degrees (F), hot enough to cause dangerous third degree burns to just about anybody who spilled their coffee on themselves, even through clothes, IN JUST 3 SECONDS! Liebeck endured third-degree burns over 16 percent of her body, including her inner thighs and genitals—the skin was burned away to the layers of muscle and fatty tissue. She had to be hospitalized for eight days, and she required skin grafts and other treatment. Her recovery lasted two years. Adding insult to injury, the trial revealed that over 700 other people had previously suffered similar consequences to Stella from spilling McDonald’s boiling hot coffee on themselves, BUT McDonalds had made a strategic decision to withhold that information from the public and the appropriate regulatory agency, the CPSC, by quickly settling all prior lawsuits and demanding plaintiffs sign a Non-Disclosure Agreement (NDA), which prevented anyone from talking about the settlements, their injuries and thus, helping to perpetuate the obvious lie that McDonald’s hot coffee was a known, obvious hazard requiring nothing more than a mild “Coffee Hot” statement on their foam coffee cups. McDonald’s, in short, chose Profits Over Safety and, as unbelievable as it sounds, to this day, McDonald’s has NOT lowered the temperature of their coffee, contending that ONLY 700 customers had burned themselves compared with billions of cups of coffee they sold annually (showing they relied only on statistical risk of injury data and ignoring the other side of a hazard analysis, namely the severity of the hazard’s potential consequences (very dangerous third degree burns). Did McDonald’s (and other fast food coffee retailers) come clean with consumers and at least warn them that their coffee was heated to a very dangerous 190 degrees? Nope. They settled for a very light warning that totally ignored the real hazard of the dangerously high temperature and, instead opted for the bland statement: “Caution: Contents Hot.”

In my opinion, this poor excuse for a warning by McDonald’s keeps the consumer totally in the dark about the real hazard from their McDonald’s coffee. And, that, folks, by definition, is a HIDDEN, NOT AN OPEN AND OBVIOUS HAZARD. The real question for McDonald’s to answer to their public is: HOW HOT IS HOT?” So far, they have not answered this question. Another example may help reinforce my point that some open and obvious claims by manufacturers may need to be re-examined.

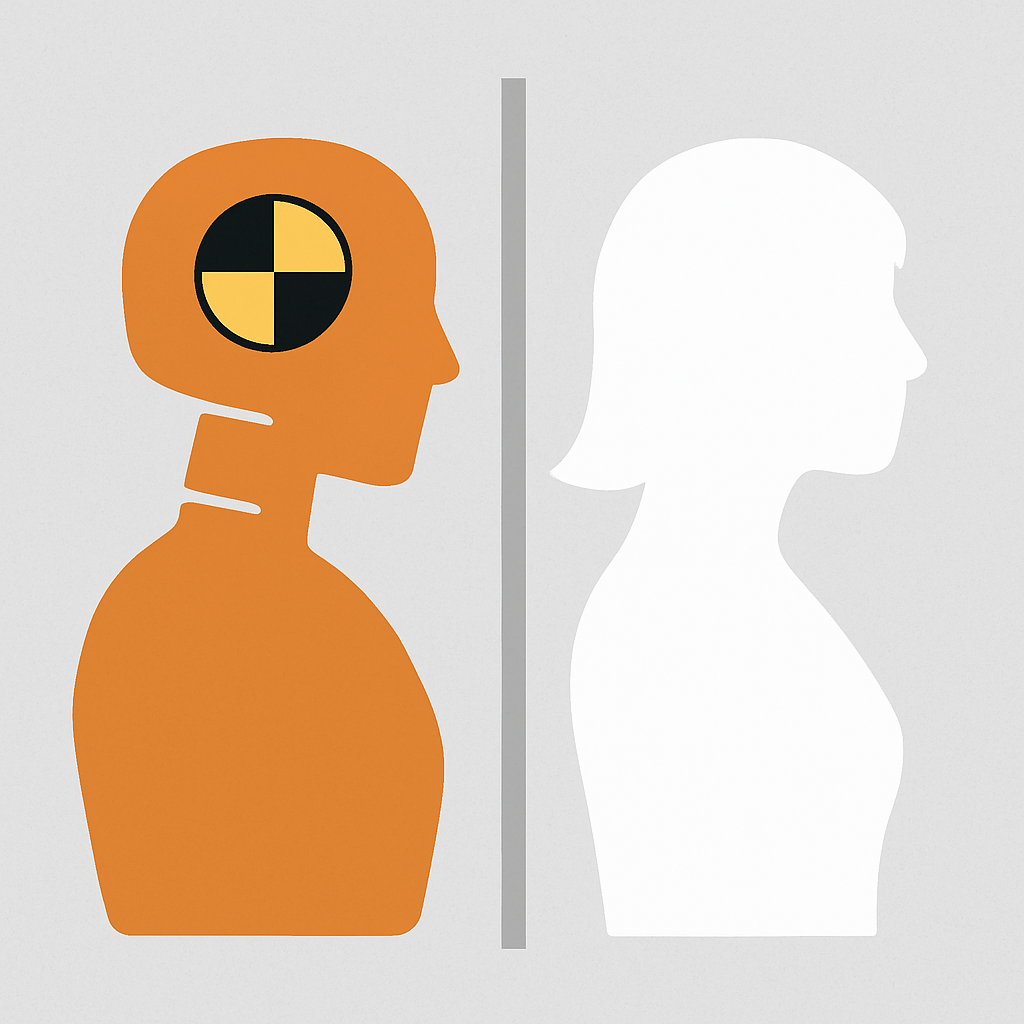

This week, I bought a new Cuisinart Blender/Food Processor with a warning on the cardboard protective wrap surrounding the blade (and again in their instructional manual) that the blade was dangerously sharp and must be avoided by human contact. This raises the question, like McDonald’s, HOW SHARP IS SHARP? While this seems to go against the very example law schools now use to illustrate open and obvious hazards, it actually is a legitimate question. I was recently hired in a case where a woman lost a digit while using her new Mango Slicer to cut her mango. Examination by expert engineers and designers of such products has revealed that the manufacturer’s blade was not just “knife sharp” but by several degrees, very dangerously sharp to the point it might have been confused with a guillotine. Finally, in the construction example I referenced earlier, a hazard that may be open and obvious to trained, certified, well informed equipment operators and supervisors may not be open and obvious, and, in fact, totally hidden, from union-supplied day laborers who undergo no such training. Equipment manufacturers like to blame (as they should, especially with the HazCom and other communications requirements for employers to inform their employees about workplace hazards) the construction company that employs these day laborers for inadequate safety protocols as well as relying on the old salt, the day laborer should have recognized the open and obvious nature of the equipment misuse on his or her own, even if the immediate supervisor gave an order that placed the employee in harm’s way....except that he wasn’t aware of his dire situation at the time. In effect, the dangerous assignment which exposed him to risk of serious injury or death was “hidden” from him. I agree that the first responsibility for warning the employee must come from the employer (the construction company). However, a manufacturer who places warnings about claimed “open and obvious hazards” in their operator and general safety manuals (neither of which, most day laborers ever see or read), should also consider, almost as a warning of last resort, placing a prominent, conspicuous warning on its equipment (as they typically do for other warnings that appear in their manuals) because they know or should know that not all construction companies fulfill their OSHA-mandated responsibilities to provide a safe work place and to warn about potential hazards. Even though on-product warnings do not have an exemplary record of influencing consumer or employee behavior, this does not exempt a manufacturer from at least making the effort, acting as a “warner of last resort” to those workers uninformed about potential hazards and whose bad luck placed them at a construction company with poor safety protocols. Such warnings not only may protect the uninformed temporary worker, but they also may serve as a reminder to even those with much training, certifications and years of experience confronting equipment hazards.

I hope the above examples will teach us all that what we think or used to think of as an open and obvious hazard may have such nuance to that concept which should influence safety personnel to err on the side of caution and provide warnings for such cases. Each situation calls for study and research and serious discussion that balances the need to avoid warning dilution, while, at the same time, not hastily dismissing such situations as not requiring warnings because of the claimed open and obvious nature of the hazard.